Our real job is not just charting our own potential, but it’s finding it in others around us. This article is one of a series of stories about ordinary people who have overcome adversity to do great things. Reading or witnessing them do remarkable things can inspire us to bend our potential arc, and others.

Growing up in a small village in Ireland I had never heard of Ernest Shackleton or his epic exploration in Antartic. I had no idea when I got married in Kilkea Castle that the local hero was someone I would learn about twenty years later in Harvard Business School. As an immigrate I find myself yearning for positive, inspiring stories from home. And this was it! In class in 2019, I discovered the explorer Ernest Shackleton and how he made himself capable of doing the impossible. The more I learned about him and his team on the Endurance’ expedition (1914-1916) the more compelling his story became to me.

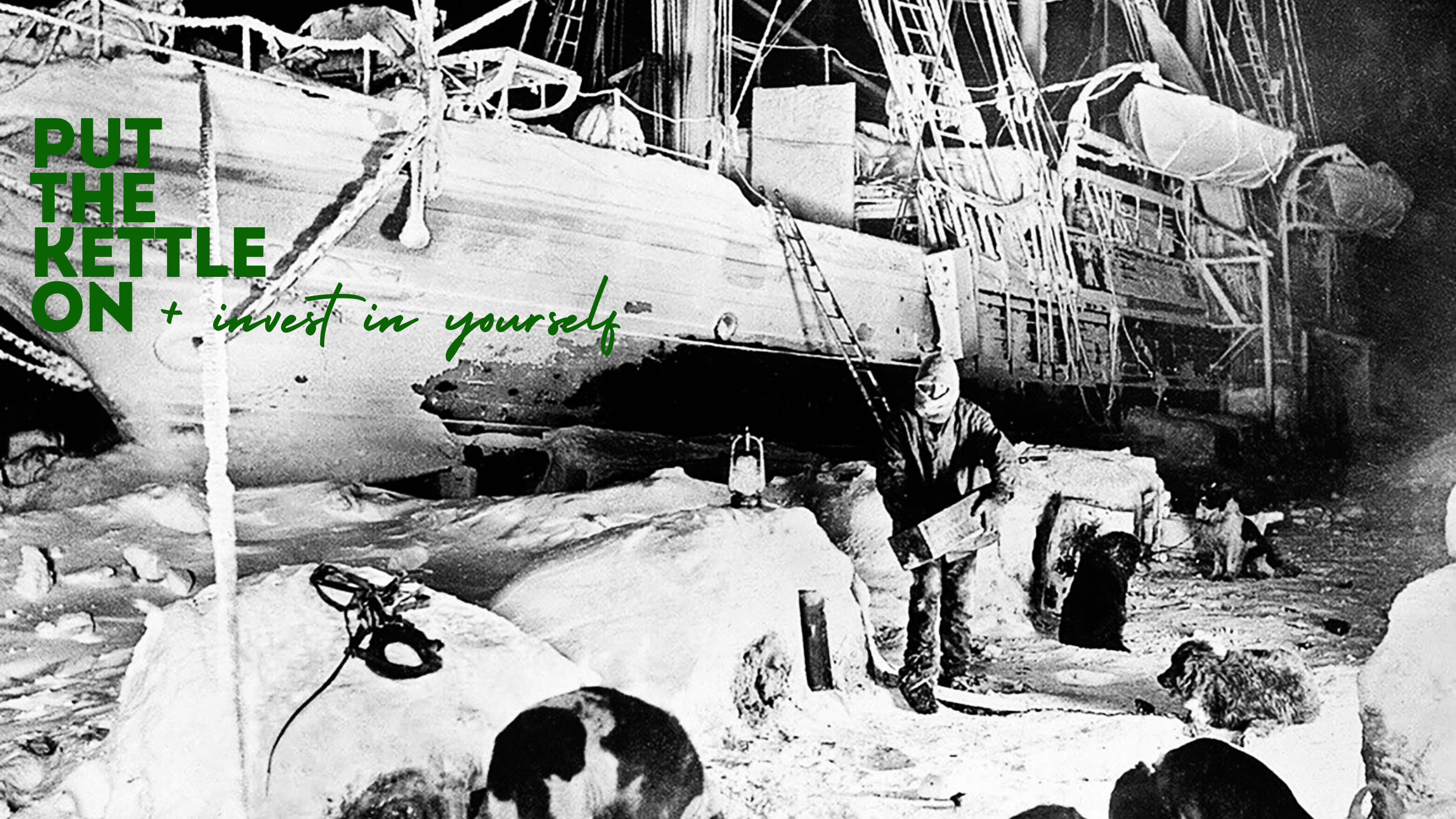

His ship stuck in ice in Antarctica in 1915, the crew were trapped with no communications to the outside world. The vessel was sinking below the ice and the 28 men left of the iceberg with only three lifeboats, a small supply of canned good and their leaders determination to bring them home, alive!

As I read and learned about my local hero story, it became apparent that he was a gift of leadership inspiration I had yearned for.

As we return to the office after the pandemic, we face our own challenges. Here are some of the most important lessons I have drawn from my neighbour Shackleton. I hope it helps you navigate your journey today – as much as it did me.

Lesson 1 :: In times of volatility, hire for attitude + train for skill.

Shackleton understood that in the life-threatening conditions of the Antarctic, he needed people with optimism, perseverance, cohesion, adaptability, humour, and dedication to get the job done.

He had hundreds of applicants to choose from, and he accepted and rejected men based on these attributes. He looked to create an integrated team :: a diverse cast of capabilities, traits and strengths that would work well together under conditions of great uncertainty and high stakes. No matter what industry you come from, leaders today can learn from the importance Shackleton placed on assembling his team and how he did this. In times of crises, resumes tell us less about the right fit between a person and a position than attitude, character and grit. Hiring your team is more than filling individual positions, we are trying to build a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. 2 + 2 = 22!

Lesson 2 :: Show up in service to your mission.

Shackleton knew that in a crisis his team read cues from his presence, including his voice, energy, and whether he appeared focused, positive and confident. He was careful each day to use his body language and bearing as productive signals to his staff. For example, each morning he emerged from his tent with his shoulders back and his head up. He did this even on days when he documented inner fears and frustrations in his diary. He displayed outer determination, strength and empathy to his team. I read a powerful example of this grit on November 1915, the day after the Endurance finally sank through the ice and disappeared, he served his men hot tea, gathered them and said confidently, “Ship and stores have gone, so now we’ll go home.”

Those of us in positions of authority today can take a page from Shackleton’s book – we must be conscious of and disciplined about how they show up to all those who look up to us. This will ground and fortify our people and help them do their best in intense volatility.

It’s important to note that showing up with focused energy and confidence does not mean leaders are not allowed to expose our vulnerabilities. We are still human beings with their our own anxieties and doubts. Being aware of and then releasing such emotions are vital. Courageous leaders understand this; they access emotional awareness and discipline to recognize their feelings and express them in carefully chosen circumstances that won’t frighten or discourage followers and jeopardize the mission. For example, Shackleton used his diary to express many of his negative emotions. But he also confided in Frank Wild, his trusted second-in-command.

Lesson 3 :: Focus on team morale + energy, foster cohesion + a sense of purpose.

In a crisis fear and uncertainty can easily destroy team unity and deplete energy. So, Shackleton kept a close eye and ear on both, inventing an itinerary of actions to keep his men’s spirits and camaraderie as strong as possible. For instance, once the ship was trapped in ice in early 1915, he required all crew to meet after dinner each night for conversation and games. This was designed to keep them engaged in an ongoing interaction, which he regarded as a key safeguard against worry, despair, and moral collapse. Shackleton recognized that this diversion was essential to his, and his team’s morale. He once pulled pages from the encyclopedia he salvaged before the ship sank to initiate conversation. He asked the crew to play his banjo, calling the instrument “mental medicine.”

Today, as leaders we can take this lesson from Shackleton and apply it to our teams. Strong morale and team unity create other important benefits: less fear, better focus, more creativity, and dedication, all of which are more likely to result in positive outcomes navigating the crisis.

Lesson 4 :: Keep your friends close + your enemies closer.

Shackleton realized that in high-stakes situations, naysayers and negative team members sow doubt and dissent among their colleagues and have the potential to sabotage the mission. When the men’s survival was at stake, he could not afford these possibilities. So, he consistently kept close tabs on the “doubting Thomases,” trying to co-opt them when he could and, when he could not, minimizing their influence. He did this by soliciting their input, by inviting them to his tent, where they could feel important by sharing quarters with the commander. In April 1916, when he sailed one of the lifeboats 800 miles for help, he took three of the naysayers with him on the harrowing journey, so they could not spread doubt and dissension among the 22 men left behind.

Most of us have a few people who exercise negative influence. In intense turbulence, it is essential to mitigate the destruction these individuals can create: first, by trying to bring them inside the tent, so to speak, and if that fails, by removing them, if possible.

Lesson 5 :: Feed + water yourself every single day.

Leading a group through a crisis is grueling work, its physically, emotionally, and mentally demanding. It is essential that we take good care of ourselves; after all, if we fail, our missions and organizations become vulnerable.

Shackleton knew this, and he made time each day to meet with himself, sometimes pacing the ice at night to sort his thoughts and feelings out, on other occasions, writing in his diary as a way of clearly his head and grounding his emotions. He made sure that he and the men had the best possible nourishment; when spirits flagged he would order hot milk served to everyone.

Today’s leaders would do well to use this tool from the Irish Antarctic explorer and make time and space every day to take care of ourselves. Sleep as much and as well as we can. Eat as well as we can. Take at least two real breaks from our gadgets during the day. Be sure to get up and move at least every 90 minutes and try to walk outdoors once a day. We should try to build in regular recovery time in which we do something joyful: paint, play the piano, take a bike ride with a loved one, sing at the top of your lungs in the shower. Try to practice gratitude by thinking of three things each day for which you are thankful. If we do this a few times, we will discover that gratitude is a feeling that grounds us as it connects us to others. This is empowering.

When, at last, Shackleton delivered the crew of the Endurance safely back to England in 1916, he had no idea that his legacy would be so important or enduring. But it became both. This determined, courageous, and creative leader did more than save his men against extraordinary odds, in doing so he helped create a toolkit of behaviors, actions and insights that can serve each of us in a world of ongoing crises.

If you plan to visit Ireland, please be sure to stop by the Shackleton Museum.